Git & GitHub

"git" can mean anything, depending on your mood.

- random three-letter combination that is pronounceable, and not actually used by any common UNIX command. The fact that it is a mispronunciation of "get" may or may not be relevant.

- stupid. contemptible and despicable. simple. Take your pick from the dictionary of slang.

- "global information tracker": you're in a good mood, and it actually works for you. Angels sing, and a light suddenly fills the room.

- "goddamn idiotic truckload of sh*t": when it breaks

"I'm an egotistical bastard, so I name all my projects after myself. First Linux, now git."

- Linus Torvalds, original author of git

Git Overview

If you write code, using git is non-negotiable. In short, git allows you to keep track of different versions of your codebase, and helps your rectify differences between these versions. You can easily restore your codebase to a previous version (known as a commit), or work on multiple independent features at the same time on their own branches.

Additionally, git makes it feasible to collaborate on projects with thousands of other developers. Each developer has a copy of the source code on their own local machine, and can make changes without needing to always be connected to a centralized server. When multiple developers have made changes to different pieces of the codebase, git can automatically merge these changes together.

Also checkout Git in 100 seconds

Or for a super overkill deep dive, the official Pro Git book

A basic Git workflow

Once you have created a git repository (repo), git does not automatically start saving (tracking) changes. The edits which are saved to your local device but not to git are called your working tree. To save these changes to git, we create what is called a commit.

Before creating a commit, we first must prepare it by specifying which changes from the working tree we want to save. We do this by adding the changes to the staging area. Once we have added all the changes we want to save to the staging area, we can create a commit with a message describing the changes made.

Finally, if our local repository is also hosted on GitHub (known as having a remote repository), we can push our changes to GitHub. This will make our changes available to other developers working on the project, who can pull in our changes to their local repository.

Branches

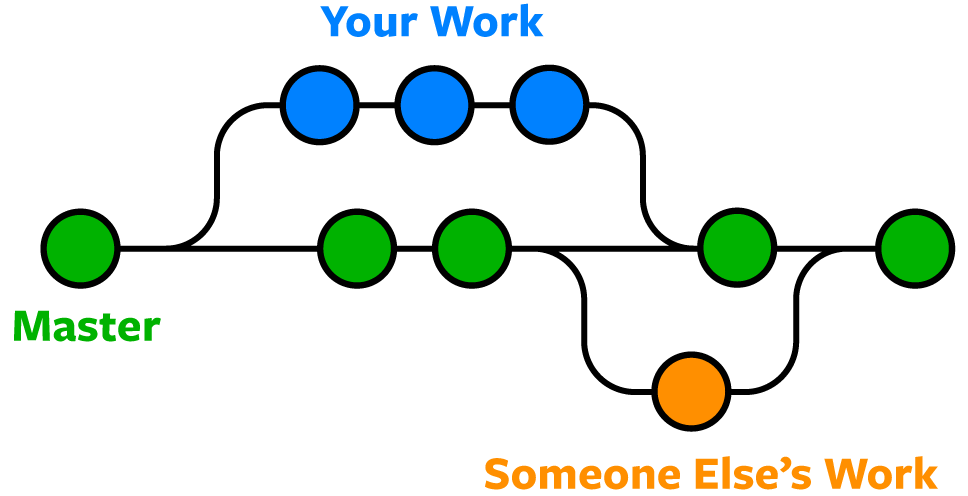

Our basic workflow of creating commits to our repository allows us to revert back to previous versions of our codebase, but it still does not help us handle the complexity of having many developers working on the same codebase. This is where branches come in.

Every repository has a default branch, typically called main or master. This default branch contains code which has been reviewed and is ready to be used in a production setting. Before directly making changes to this default branch, a developer creates their own branch to develop an individual feature or fix a bug. This branch then has its own commit history, and can be worked on without interfering with the main branch.

Once the feature branch is ready, it can then be merged back into the main branch, often through a pull request. The commits from the feature branch are then added to the commit history of the main branch or can be squashed into a single merge commit. 1

Merge conflicts

<<<<<<< HEAD

conflicting changes 1

=======

conflict changes 2

>>>>>>> conflict2

Merge conflicts occur when two branches are merged with inconsistent changes. Git does not know which changes should be kept, so it shows both changes and the developer must manually pick which changes to keep. GitHub provides an interactive UI for resolving merge conflicts, but they can also be resolved locally by deleting the conflict markers (the <<<<<<<, =======, and >>>>>>> lines) and any unwanted code in the merge.

GitHub

Git is the open source version control software which you just learned how to use. GitHub is a hosting provider that allows you to store your git repositories in the cloud. GitLab and Bitbucket are other popular alternatives to GitHub, although they have a much smaller market share.

Since git repositories are almost always hosted on GitHub, it can be easy to confuse the two. GitHub layers features on top of git, which have become essential to the modern development workflow. Understanding usage of core features of GitHub is almost as important as understanding how to use git itself.

Pull Requests

Pull requests (PRs) are proposals to merge changes from one branch into another. They can be assigned reviewers, who can leave comments and suggestions on the proposed changes. GitHub provides a diff view in the browser for inspecting modified files.

Issues

Issues are general purpose "posts" associated with a GitHub repo. Most often, they are used to report bugs or feature requests. Issues can be referenced in pull requests which address them, or be assigned to a specific developer to fix. When and issue is resolved, it is marked as closed.

Actions

GitHub actions are way of automating continuous integration and continuous development (CI/CD) tasks. For example, you can run a test suite on every pull request to make sure that it does not introduce any breaking changes. GitHub actions are defined in a .github/workflows directory in your repository and will be covered in more detail at the end of the course.

.gitignore

Very often times, files will be generated within a git repository which should not be tracked by git or pushed to GitHub. Examples include, build outputs (/build), installed dependencies (/node_modules), editor configuration files (/.vscode), or environment variables (.env). To prevent these files from being tracked, you can create a .gitignore file in the root of your repository. This file can specify exact file name, file extensions, or directories to ignore.

# Ignore a single file

.env

# Ignore all files in a directory

/node_modules

# Ignore all files with a specific extension

*.log

When you create a repository on GitHub, you will be prompted to create a .gitignore and have the option to select a template. Selecting the Node template should be sufficient for most projects you build with the technologies we cover in this course.

Global .gitignore

In addition to a project's .gitignore file, you can configure your own global .gitignore file which will apply to all repositories on your machine. This is useful for ignoring files which are specific to your development environment, such as editor configuration files. It is also useful for ignoring files which are generated by your operating system, such as .DS_Store files on macOS. To create a and configure a global .gitignore file, run the following commands in your root directory:

touch .gitignore_global # Create global .gitignore file

git config --global core.excludesfile ~/.gitignore_global # Tell git to use your global .gitignore file

code .gitignore_global # Open the global .gitignore file in vscode

Git Quick Reference

Check out the GitHub and GitLab official cheat sheets for a more comprehensive reference.

git init - Initialize (init) a git repository

If you are starting a new project, this is likely the first command you will run, unless you are cloning an existing repository onto your local machine.

git init

git status - Check the status of your repository

Shows you which files have been modified, which files are staged for commit, and which files are not tracked by git.

git status

git add - Add files to the staging area

Files must be staged before they can be committed. Most often you will use git add . to add all files in the current directory.

git add . # Add all files in the current directory

git add file1.txt file2.txt # Add specific files

git commit - Commit changes to the repository

Think of making a commit like saving your changes. At any point, you can revert back to a previous commit (or save) or jump between commits.

git commit -m "All commits must have a message"

Be sure to use descriptive commit messages so that it will be easy to understand what changes were made when looking back at the commit history.

git remote add origin - Add a remote repository to existing local repository

Use this command you have a local repository, and want to push it to GitHub. First create the GitHub repository to get the remote URL, and then "add" the remote URL to your local repository so that you can "push" your changes to GitHub.

# Replace the URL with the URL of your repository

git remote add origin https://github.com/CS61D/my-repo.git

git push - Push changes to a remote repository

If your local repository is also hosted on GitHub, this will push your local changes to GitHub. You may sometimes need to pull the latest changes from GitHub before you can push your changes.

git push origin main # Replace main with the branch you want to push to

git clone - Clone a remote repository

If a repository is already hosted on GitHub, you can clone it to your local machine to be able to work on a local copy.

# Replace the URL with the URL of your repository

git clone https://github.com/CS61D/my-repo.git

git pull - Pull changes from a remote repository

git pull origin main # Replace main with the branch you want to pull from

git status - Check the status of your repository

Shows you which files have been modified, which files are staged for commit, and which files are not tracked by git.

git status

git log - View the commit history

Each commit has a unique hash, a message, and the author. You can use the hash to revert back to a previous commit.

Sometimes you may see a full 40 character long git hash like 762d1585e4075dc8dcee917fc8727ea70365989f, and other times you may see it truncated to just the first 7 characters like 762d158. The full hash is always unique even across repositories. The shortened hashes are only unique within a single repository. You can typically just use the short hash to refer to a commit.

git log

git log --oneline # View a simplified log with only the shortened commit hash and message

git branch - Create, list, or delete branches

git branch # List all branches

git branch new-branch # Create a new branch

git checkout -b new-branch # Create a new branch and switch to it

git branch -d branch-name # Delete a branch

git checkout - Switch branches or view a previous commit

git checkout branch-name # Switch to a different branch

# Check out a new branch from a previous commit hash

# Find the hash of a commit by running `git log`

git checkout -b new-branch 762d158

git restore - Discard changes in working directory or unstage files

git restore file.txt # Discard changes in file.txt. Revert contents back to last commit

git restore --staged file.txt # Unstage file.txt, undoing `git add`

Running git restore on a file is irreversible. An alternative is to stash the changes, which allows you to bring them back later.

git stash - Temporarily store changes

git stash # Stash all uncommitted changes

git stash pop # Apply the most recent stash

git stash list # List all stashes

git stash push file1.txt # Stash only file1.txt

git merge

Merge changes from one branch into another. If you make a pull request on GitHub, then "merging" the pull request will automatically merge the changes from one branch into another, meaning you often do not have to run git merge locally.

# Merge other-branch into current branch

git merge other-branch -m "Merge commit message"

git merge other-branch --no-edit # Use default merge commit message (recommended)

(Todo talk about merge conflicts)

git diff

View the difference between two commits. If you make a pull request on GitHub, you will automatically be shown the differences between the two branches, meaning you often do not need to run this command locally.

git diff other-branch # View difference between current branch and other-branch

git diff other-branch file1.txt # View difference between current branch and other-branch only for file1.txt

Footnotes

-

There is also a third popular option called rebasing. The differences are not particularly important for our purposes, but you can read the Github docs

on all the ways to merge in a pull request. ↩